There has been no testing of wastewater for COVID-19 so far in the Interior Health region.

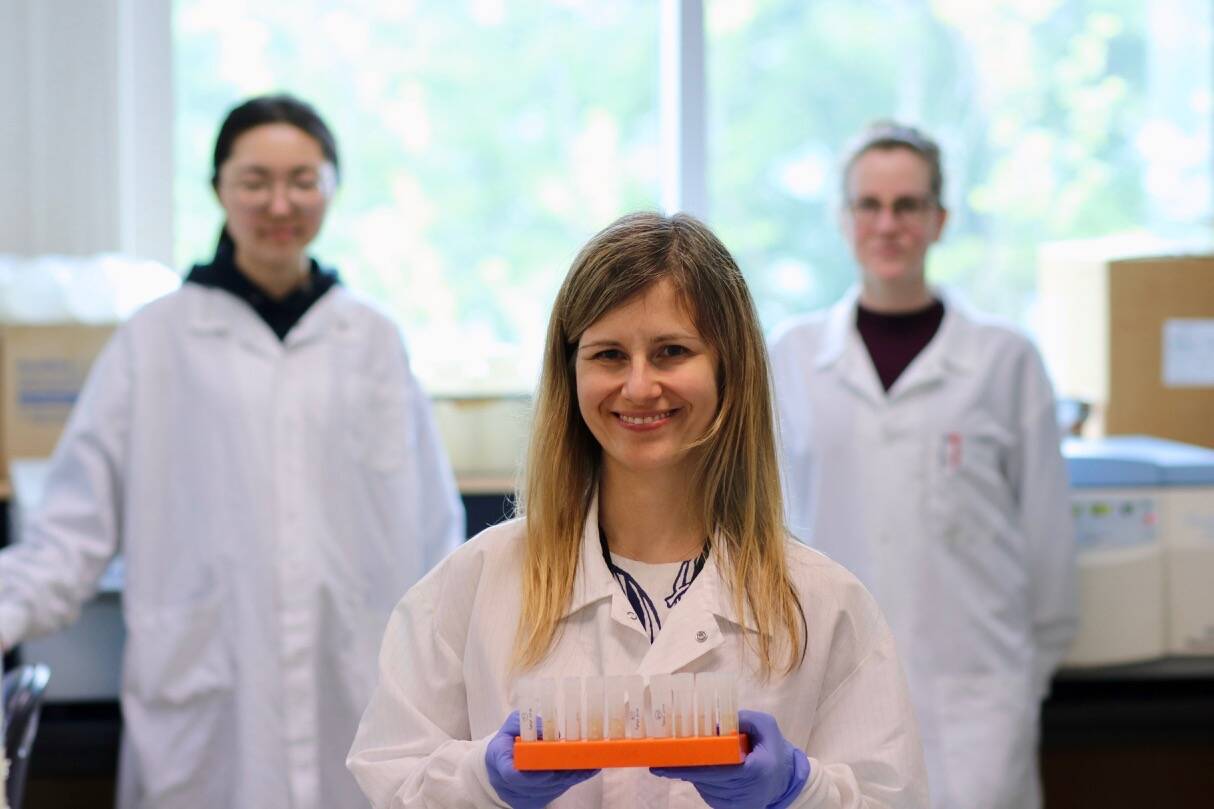

But a testing site will be set up within the next few months at an undecided location, according to Natalie Prystajecky, an environmental microbiologist at the BC Centre for Disease Control.

The COVID-19 virus is present in the feces of people infected with it, and this can be detected in wastewater at a sewage treatment plant.

The results can indicate the amount of virus in a community.

Wastewater testing can not show the number, or the identity, of people who are infected or are contagious, Prystajecky says. But it can tell us whether cases are rising or falling in a community, and it can identify and track outbreaks.

The BCCDC has five test sites at wastewater facilities in the Lower Mainland. In total those projects test about 50 per cent of the province’s population.

But if the new IH project is set up in Kelowna, for example, the test results would not indicate anything about COVID-19 anywhere else in the health authority, which includes the Okanagan, Kootenays and Thompson-Cariboo regions.

Test results depend on many hyper-local factors. For example, wastewater in different treatment plants will vary in their concentration of industrial or business wastewater, which will affect the results. Different locations also may have different waste treatment technologies, or different weather.

“You can imagine that the Lower Mainland, where there’s a high rainfall, is different than northern Alberta, where you have freezing temperatures,” Prystajecky says.

Testing in the Lower Mainland is done several days per week, one test every hour.

“You have to take into account how variable wastewater can be over the course of the day. You can imagine that there’s different inputs in the middle of the day and at the end of the day,” Prystajecky says, “and we also sample multiple times a week, recognizing that weekdays and weekends can be different.”

So testers look at trends over time, rather than absolute individual numbers.

“Is a trend increasing, or decreasing, or is it stable?” says Prystajecky. “And how is it compared to last week and the week before?”

Across Canada, as the availability of PCR testing decreases, wastewater testing is becoming more important, along with other indicators such as hospitalizations and ICU rates.

The goal of public health agencies across the country is to have 80 per cent of the population covered by wastewater surveillance, according to Prystajecky. Even though certain pockets might not be tested, health authorities would get a sense of the COVID-19 activity at a provincial scale.

Prystajecky says a single wastewater test is more expensive that patient testing because it takes more labour and equipment.

“But the nice thing is that with a single test, you’re testing the population of 20,000 people or 100,000 people. So it seems expensive at the sample level, but for the scale of the population you serve, it’s good value for the money.”

Related:

• Canada needs a stronger COVID-19 detection system, experts say

• Interior Health region on COVID-19 pandemic recovery path

• Flushing out COVID spread: wastewater signals can be useful tool as testing declines

bill.metcalfe@nelsonstar.com

Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter