Editor’s Note: The city of Ocean Shores formally applied for Federal Emergency Management Agency funding for its first tsunami vertical evacuation structure. The city met its initial deadline by completing the application on Nov. 28, two days ahead of schedule. The application now is being reviewed by the state Emergency Management Division before it is submitted to FEMA in January. The following article is from the Emergency Management blog.

By Steven Friederich

State Mangagement Division

Ocean Shores, like most of Washington state’s coast, will be prone to a tsunami when an earthquake strikes off the Strait of Juan de Fuca – or even a distant tsunami like Japan or Alaska. But getting to high ground is going to take a hefty walk for many residents. And, for a city that boasts a lot of retired residents, the concern is real.

Earthquake Program Manager Maximilian Dixon with the Washington Emergency Management Division has been working with city officials for months now to help cultivate the support needed to move forward with plans to design and ultimately construct a vertical evacuation structure designed to withstand earthquakes, aftershocks, liquefaction and multiple tsunami waves.

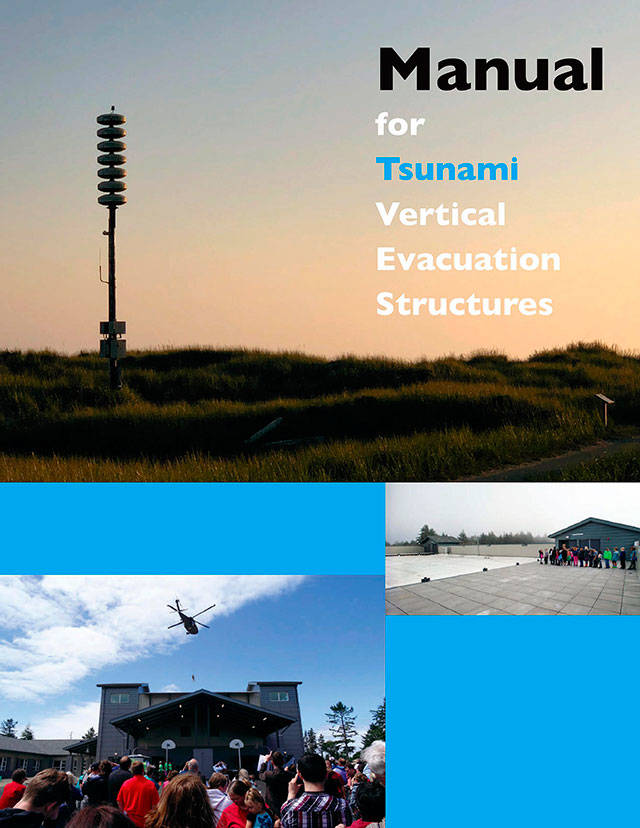

Now, Dixon, working with researchers at the University of Washington, has developed a manual that will help any coastal city, county or tribal entity figure out what it would take to design and then build a similar project.

“Our state has the second highest earthquake risk in the nation and we do a great job talking about our tsunami threat, but we really need community support, local champions and we hope this manual will help us generate that interest,” Dixon said.

The manual will help champions work with their local governments showcasing the different funding mechanisms that could be used for construction and design, including the possible grants that are available – and the specific notations that need to be added into planning documents to help qualify for those grants.

In June, the Shoalwater Bay Indian Tribe received $2.2 million in federal funding to help pay for the construction of a safe refuge for hundreds of residents. This was the first time federal funding from FEMA had gone toward construction of a vertical evacuation structure in Washington state. Previously, the state worked with local jurisdictions in Long Beach and Pacific County Fire District 1 at Ocean Park to do design work toward potential vertical evacuation structures.

“The success from our partners in the Shoalwater Bay Indian Tribe proved that federal dollars are out there, not just for design, but to construct life-saving towers, berms, buildings and hybrid structures,” Dixon said.

The first tsunami vertical evacuation structure in North America was unveiled in 2016 at Ocosta Elementary School near Westport. School district officials applied for federal funding and were determined to be eligible by FEMA, but didn’t get the funding. Instead, taxpayers voted to foot the entire bill, noting it was critical to protect the kids.

The new “how-to” guide helps jurisdictions figure out how to navigate the bureaucracy and, hopefully, help get more projects off to a better start. The 100-page manual provides a seven-step process and a check list to help as the process moves along.

Phase 1: Involve Emergency Management Partners

Phase 2: Assess Tsunami Risks and Current Evacuation Options

Phase 3: Engage the Community

Phase 4: Identify and Evaluate Potential Sites

Phase 5. Develop a Funding Plan with Alternatives

Phase 6. Assemble Project Team, Complete Design, and Confirm Budget

Phase 7. Oversee Construction, Completion, and Operation

Researchers from the University of Washington worked with Washington Emergency Management Division and the state Department of Natural Resources on two forums in the spring in Grays Harbor County to come up with ideas to help streamline items needed for the manual. In addition, a research team from New Zealand also conducted focus groups in Long Beach, Tokeland, Westport and Ocean Shores to provide insights into the process of developing community-led, agency-supported vertical evacuation structure development.

At the forum in Ocean Shores, a survey of attendees found that 87 percent had a “strong certainty” that tsunami vertical evacuation structures could save their lives and the lives of the people in their community. And nearly half of respondents looked to their elected officials and emergency managers for leadership and acknowledged local funding would need to be part of the solution.

“The process in Ocean Shores is progressing and I’d say they’re about step four in the process,” Dixon said. “We’re definitely using what worked on other projects to help them along. Each time we have a successful project, it will help everyone else get through the steps easier.”

The manual suggests that as more structures are completed, there will be more available cost information and a better understanding of the process.

“These are costly projects for communities with limited resources, and some communities will require multiple structures,” the manual notes. “Those interviewed expressed support for approaches that could reduce project costs. For example, towers may provide the most commonly used vertical evacuation option, particularly for communities that need many structures. Developing a prototype tower design could reduce project costs. Such a tower design could be appropriately modified for various site conditions, height requirements, and appearance criteria. The design could be optimized to use common steel shapes and connections to increase efficiency during design and construction. Similarly, tsunami modelers could be commissioned to model a variety of typical coastal sites and to determine tsunami depth and velocity for design purposes. These approaches may also work with berm design.”

The NOAA/National Weather Service Tsunami Activities Grant provided funding for the manual.

Steven Friederich is a former reporter for The Daily World and former Vidette editor.